Growing up I loved mystery books and TV shows. My mom liked to watch Dateline reruns or Law and Order SVU while cooking dinner, and when we came home from school, my sister and I would sneak into the kitchen and watch the copies of Nancy Drew we held in our backpacks. It is no surprise that true crime is my favorite creative non-fiction podcast genre.

It is a known fact, documented or otherwise, that women love true crime. Maybe it’s the feeling that listening to the brutal death of another woman will prepare us in case we ever get kidnapped by a serial killer. Maybe it’s the feeling of justice that calms us in a world where injustice happens to women every day.

True crime podcasts capture my attention because the stories are compellingly told. Mysteries at large are written and designed as a roller coaster, and true crime podcasters build this into the auditory realm—the original method of human communication—to deliver darkness in a more captivating way.

There are deeply rooted colonial problems inherent in the storytelling of most true crime podcasts, and, unfortunately, this colonization of the genre has been perpetuated by its auditory style. Historically, a majority of stories told have been of white, cis-gendered female victims slaughtered at the hands of a monster who is made into some kind of evil genius revered for their violence.

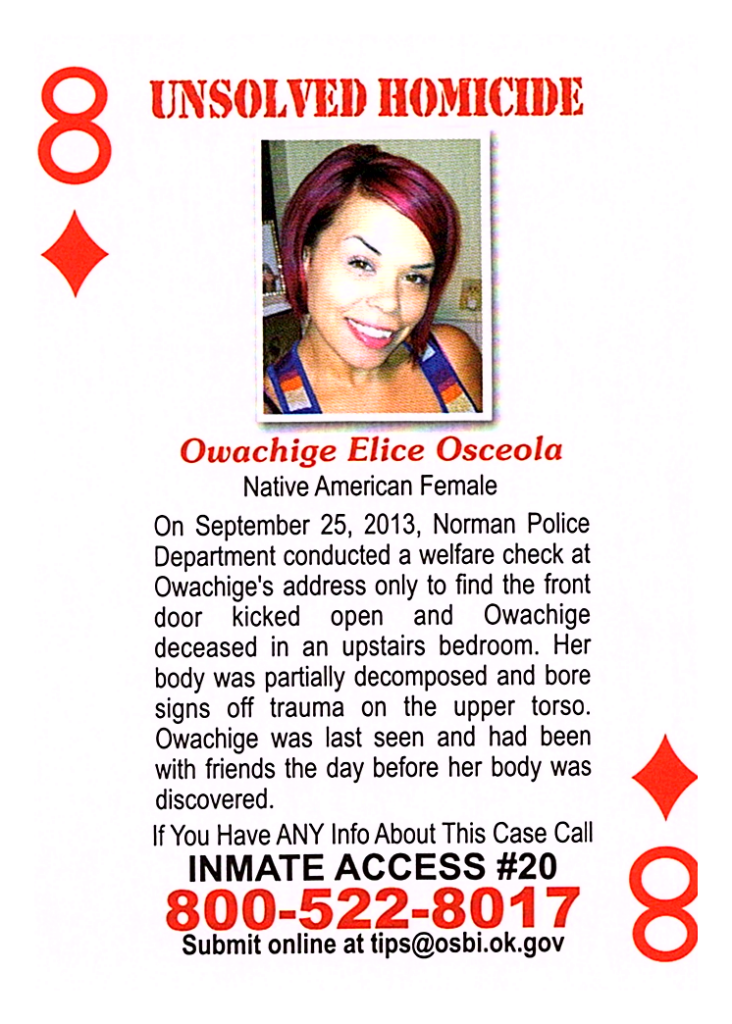

The hero versus villain scenario has been played out a thousand times—sometimes with ambiguity over who plays which role: the victim or the killer. Murders are often contested over which killer was the most brutal and which victim suffered the most. Stories of missing and murdered Indigenous, Black, and Brown women, transgender women and other members of the LGBTQIA community, and so many other marginalized groups are forgotten and replaced. Gabby Petito is a household name that enraptured the public, mainstream media, and hosts of true crime podcasts across the country. While her murder was horrible and should not be forgotten, it was sensationalized and widespread in a way that Owachige Osceola, a Native American woman murdered in her home in Oklahoma, wasn’t—until host Ashley Flowers told her story on her podcast, The Deck.

True crime is complicated and horrible; there is no denying that. It is so strange that people, myself included are so easily captured by stories of distressing violence and brutalism. However, true crime is also a genre that demonstrates how rhetoric enhances fact and makes a brutal story more compelling and important to the public. Within the violence, there is beauty in sharing the stories of forgotten victims and their families. Moreover, there is beauty in the way thousands of people can come together over one story and work together to keep a person’s story alive long after they are gone.

Links

Links